Matthew Wren's Benefactors Book

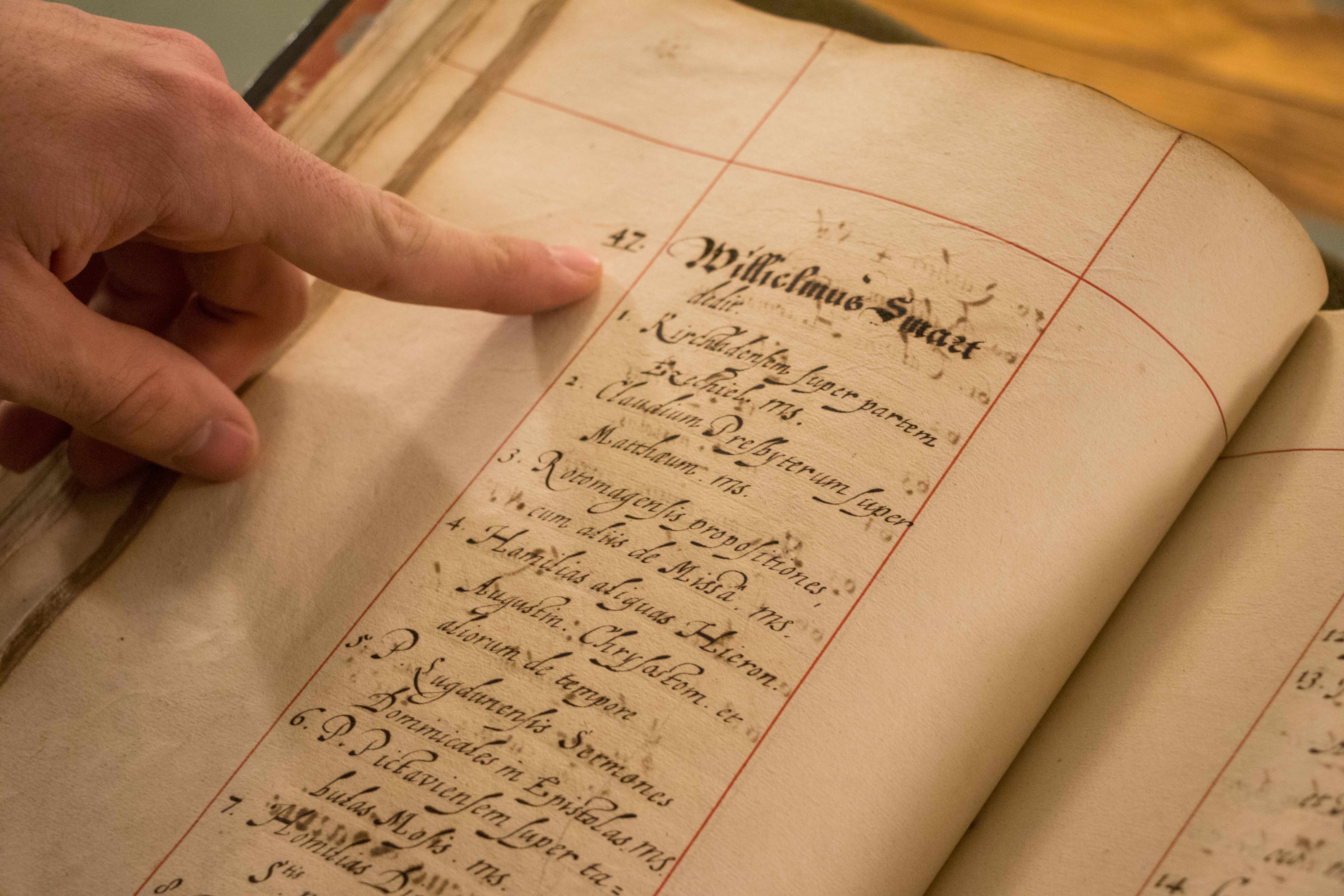

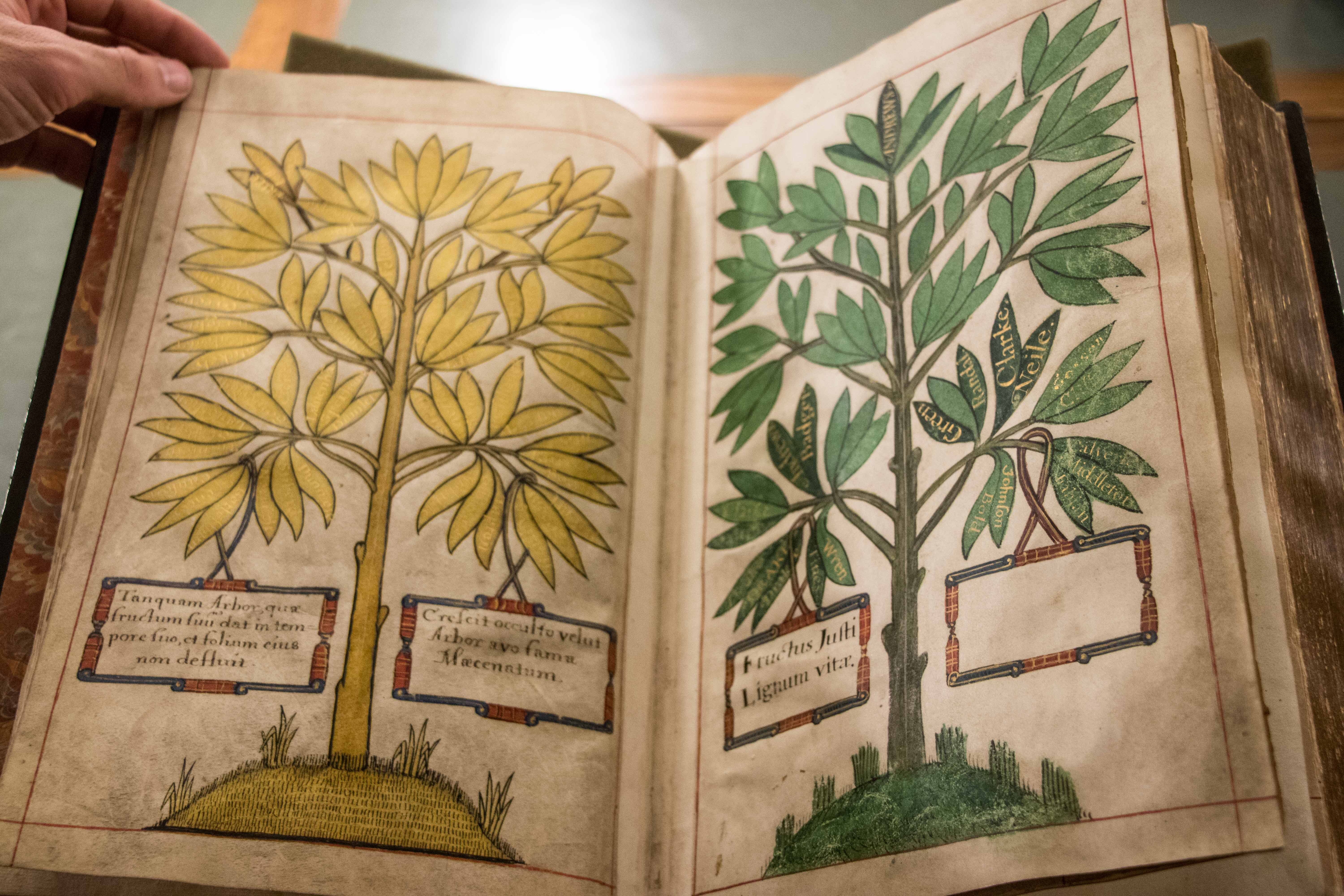

As of last week, the Matthew Wren Benefactors' Book has been added to the Cambridge Digital Library. As many people will know, the library is so much more than a reading room. Among other things, it also contains many of the College Treasures. One of these treasures is the Matthew Wren Benefactors’ Book. Kit Smart spoke to Jonathan Nathan, who has been working to transcribe, translate and understand the book. It is a striking manuscript, with beautifully detailed illustrations of names and coats of arms, and a stunning double-page spread of gold and green leaves with the names of benefactors painted upon them. But what is this book? There are two answers to this question. Firstly it is, materially speaking, a list compiled by Matthew Wren, then-President of the College, of books given to the College by benefactors. The question of why it exists, and what it meant to Wren and his successors, is far more complex. What is clear is that the book is one of the best sources we have for the library in its early stages, thanks to Wren’s efforts to compile a list of medieval books and their sources, such as at least eighty manuscripts given to Pembroke by a man named William Smart. Smart’s gift, from the abbey of Bury St Edmunds, represents the most intact monastic library surviving in Britain.

Smart's gift of manuscripts represents the most intact monastic library in Britain today

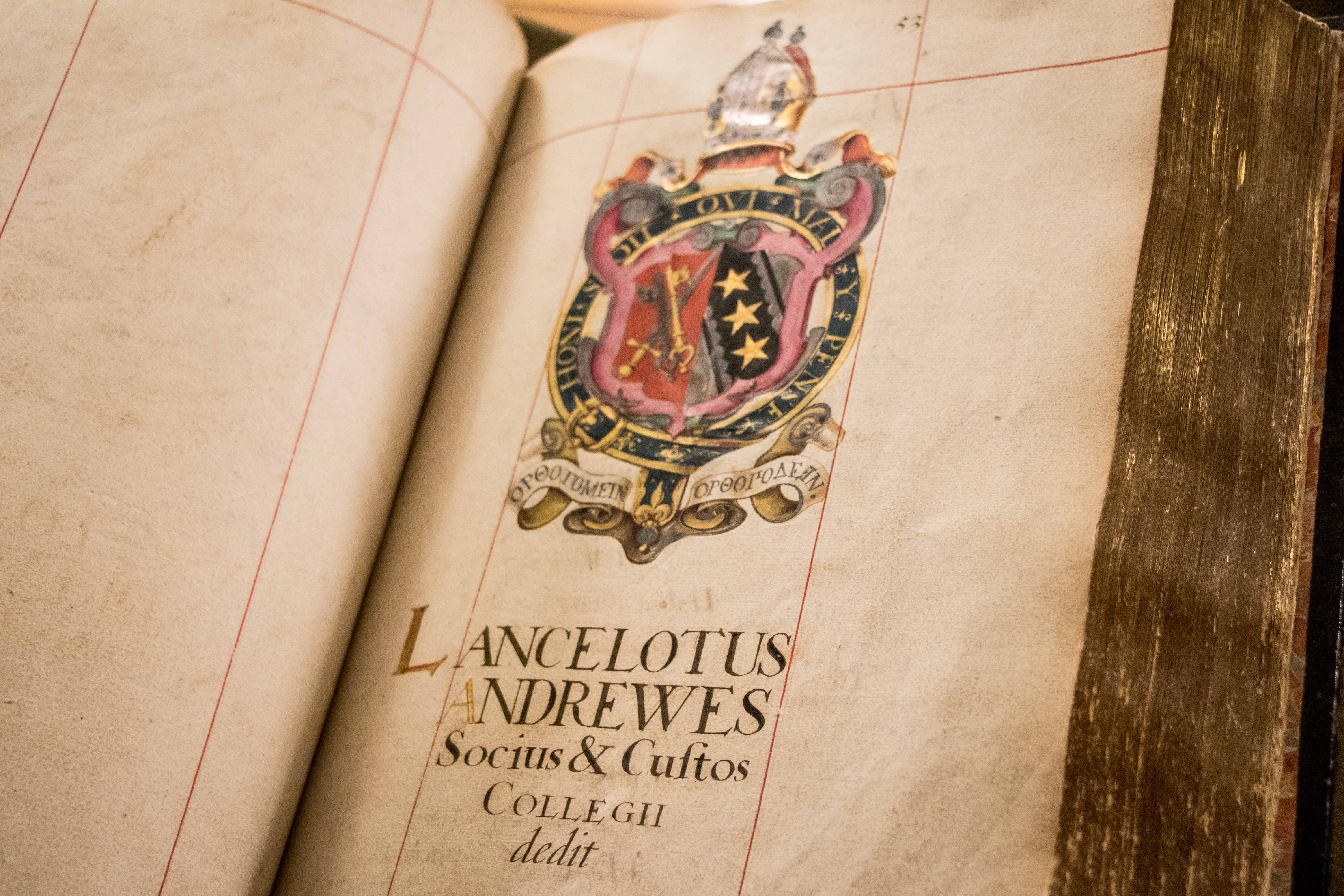

Wren then set to recording contemporary donations. There are lots of curious details; dates that don’t match up, for example, that make the book an intriguing mystery for Jonathan to unravel. An entry that particularly stands out is the record of Lancelot Andrewes’ donations. He was Wren’s patron and mentor from 1602, and he gave over 300 beautiful books to the College. The size of his crest and the skill with which it was clearly committed to the page reflects this.

Andrewes' elaborate entry in the book reflects the importance of his gifts

The book lists the majority of important Fellows and Masters from 1617 to the mid-18th century, and some of our most precious gifts, like Abraham Ortelius’ Album Amicorum – arguably our most valuable book in terms of historical interest. But we don’t just see names; the books that donors gifted to the College provide a record of what interested them, and what the College most needed and used. Jonathan points out that it can also give us hints to the wider religious culture of the time: “In the early protestant days you weren’t really meant to commemorate the dead. It was seen as too closely associated with Catholicism. Praying on behalf of the dead was something you did only if you had a cosmology where purgatory existed and prayers could affect intercessions. That’s something that changed right around the period that these benefactors’ books began to be written. The commemoration of dead benefactors began to emerge more fully. This tells us about the evolution of human attitudes to what you do with people who are so important to you, but whom you don’t have access to anymore. There’s also the religious question of whether this is acceptable at all.”

The colourful pages bearing names of benefactors

So what is Jonathan doing? Firstly, he has transcribed and translated the entire manuscript; no small task. Secondly, he is identifying the shelf mark of every book in the manuscript. Pembroke library’s tools and records help considerably, but it is still a significant task and not always simple. And then we come to the second part of answering ‘what is this book?’. This question, Jonathan argues, is impossible to fully answer without knowing what the book was made for. It seems simple; it was made to record donations and encourage future benefactions. However, this raises the question why Wren didn’t start a similar book when he became Master of Peterhouse, and why he dedicated so much time to the scholarly work at the start of the book. Jonathan has therefore been looking at other Colleges. Most Oxbridge Colleges founded before the mid-17th century have books like this, but theirs differ. He describes it as more of a fad than a joint decision, and there is clearly a long way to go before the answer as to why this book exists becomes clear. Jonathan is sure, however, that the answer is out there: “It’s an historical problem but one I think that has a solution. You don’t make an illuminated manuscript for no reason in the 17th century. It’s not something you do for the sake of record; it’s extremely expensive and laborious, so the colleges must have had some other pressing goal in mind.”

Jonathan with the book

One thing is clear: this is a beautiful and valuable record, and whatever Matthew Wren’s reasons for creating it, we can be very glad that he did. “It is both clear and obscure. It is a beautifully written record of people we know lots about, but we don’t know entirely why it was made, and until you can settle that you don’t really know what it is.”

The Wren Benefactors' Book is now available on the Cambridge Digital Library, joining the Album Amicorum and E.G. Browne's Diaries.